When the Emperor Justinian succeeded to the Roman Empire in 527 AD it was already well past its best. All the western provinces-lands we now call Britain, France, Spain, North Africa, even Italy and Rome-had been lost in the previous century. What was left, the Eastern Empire governed from Constantinople, was still the most powerful state, primus inter pares. But no longer the sole hegemon it had been. However Justinian had big ideas: he would fully restore the glory of the Roman Empire. He would rebuild all the cities and defences which had decayed. He would reunite all Christians under his leadership and build a series of new churches across his domain. Above all decided “to reconquer all the countries possessed by the Romans to the limits of the two oceans”[1]

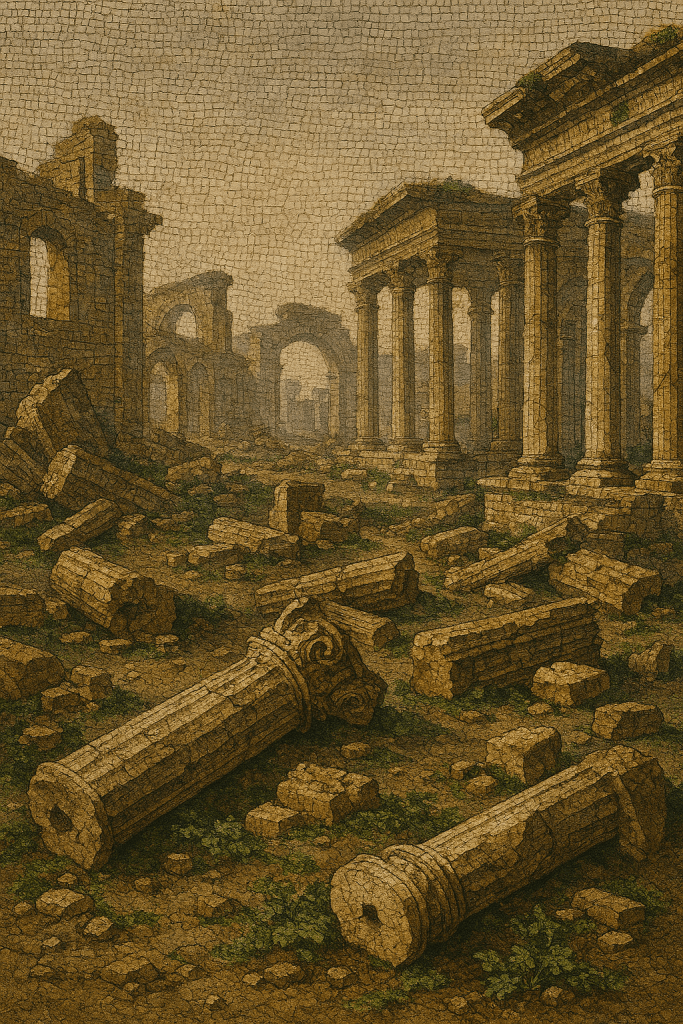

At first it went well. North Africa was captured, after a struggle. Forces were despatched as far as parts of Spain, with limited success. But it was in Italy that things started to go wrong. When Justinian became Emperor, Italy still had a thriving economy: there were big cities, Catholics, even a Pope. It was Roman in everything but name, being ruled by barbarian Ostrogoths. But names and titles mattered to Justinian. Accordingly he launched a series of wars (535-554 AD) designed to reconquer what he saw as Rome’s ancient homeland, and thereby restore its former glories. It didn’t matter that he had the help of able men like Belisarius and Narses: nor that he spent immense amounts of money and lost thousands of men; nor that he tried, and kept on trying. The contending armies swept back and forth across the peninsula, killing. taking and re-taking cities, destroying farms, aqueducts and roads. Even Rome suffered a long and disastrous siege. When the Empire finally prevailed, it wasn’t for long because the Lombards invaded in 568 AD and quickly wrested most of it away from Imperial control.

And back home did anyone thank their ambitious Emperor? Effectively, the citizens were bankrupted by the cost of all those armies, churches and palaces. Constantinople was torn apart by riots between sports fans. And the Christians, whom Justinian so loved, were divided into two irreconcilable factions, the Monophysites and the Orthodox, a feud which would have disastrous consequences for his successors. Of course Justinian was not to blame for the plague that struck the empire. But there was little left in the kitty to repair the ravages it unleashed., When Justinian died in 565AD he left the Empire larger-but fatally weakened in economic and human terms. He was a consequential Emperor, but he was a dreamer, unable to grasp that some things are truly lost forever. We shall leave the last damning words to Professor Davis

But the historian of Europe is forced to admit that by undertaking a reconquest of the West when all his forces were needed to defend his empire on the Persian and Slavonic frontiers, Justinian exhausted the resources of his Empire in pursuit of a policy which could not possibly succeed,[2]

Can anyone think of any modern parallels?

1] RH Davis A History of Medieval Europe Longman 1989 p 50

[2] ibid.p61

#roman empire #politics #economics #history #justinian #church #christianity