Who was the real St Valentine anyway? Legend says that he was a Christian citizen martyred at Rome on 14th February 269 and buried among the tombs on the Via Flaminia. Trouble is, the evidence is shaky. For one thing, the Eastern churches celebrate his day on 6th July: so what was the real date? He doesn’t even get a mention in lists of saints, compiled in the Fourth century: and even his earliest appearances occur in somewhat shaky sources [1] And the Emperor then reigning Claudius II Gothicus (not the bloke from Robert Graves) has no record as a persecutor, having many more pressing matters in his in-box [2] But whether there was a real Valentinus or not, he has left us a feast which we still celebrate today: Christians of all makes and now many non-Christians too. So with the aid of a little research we thought we’d take you back to the sort of food and drink he might have f known in that cold winter day in Rome in 269 AD.

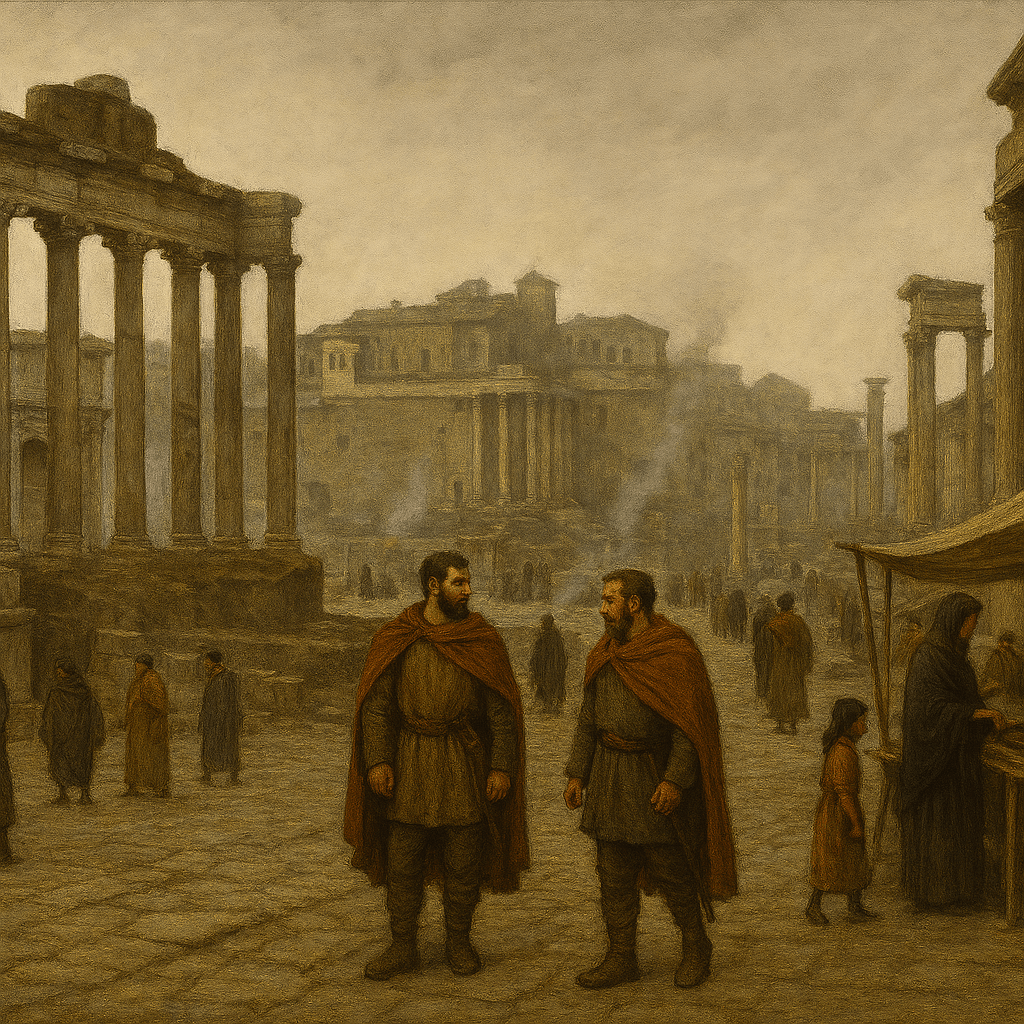

The first thing: this isn’t the opulent capital of a superpower depicted in the movies any more. The Empire has been racked by civil wars climate change and invasions for over a century. A terrible pandemic, the Plague of Cyprianus, is raging: it will carry off the Emperor and many citizens in the next few years. And Rome reflects this downturn: it is starting to look scruffy and uncared for, because the money is running out, and the Emperor is nearly always on the frontiers. But a sort of middle class, the Decuriones still survives. It’s the stratum a real Valentinus might have come from. And tonight the paterfamilias of a modest family wants to push the boat out in honour of his older brothe, who is about to return to active service with the prestigious Legio V Macedonia, in Dacia.

All the Hollywood togas, silks and linens have vanished too. People dress in rough woollen tunics with equally serviceable hooded cloaks to keep out the weather. Much is influenced by military styles: the brother even wears braccae, a curious new garment which encloses the legs in tubes of cloth joined at the top and belted at the waist. And the food reflects Rome’s beleaguered state. As this is special, there is a first course of bread (panis secundarius) and some cheese, olives and pickled vegetables. Wine is served: rough red stuff from Campania: Gaul has long been cut off by a military rebellion. It will be well watered and served in earthenware cups. The main course will be a type of stew usually made from herbs. As tonight is special, a little expensive pork has been added. Desserts are simple too: a few raisins, dried figs maybe even some honeyed dates, as Africa is still under the rightful Emperor. And the talk is not of literature or Courtesans, but of battles, taxes, and who is still alive.

Ok it’s fiction But there really was a Valentinus, this is the world he would have known. Pretty rough, pretty humble. Compare it to the pink prosecco, chocolate and lavish meals that so many will be gobbling down tomorrow. And whatever your troubles, think yourself lucky.

[1] Saint Valentine – Wikipedia

[2] Claudius Gothicus – Wikipedia

For a general history, try

Goldsworthy, Adrian. Rome: The Eclipse of the West. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003.

#christianity #st valentine #roman empire #history #church #food #drink