As 2025 draws to a close we thought we’d look back over our posts and general contributions to the zeitgeist in what has been a white knuckle ride of a year for just about everyone one on the planet. After all we do believe in recycling, don’t we?

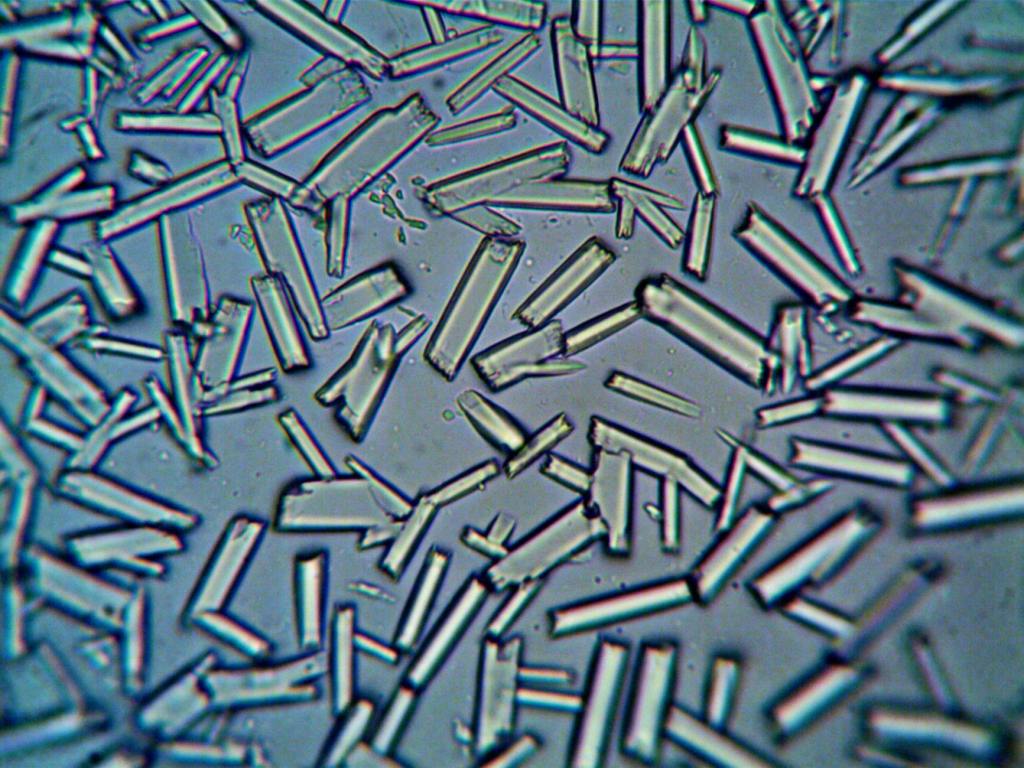

Antibiotics and the potential shortages thereof, has been a constant theme, and we think we’ve covered a story or two every month. Sources like Nature Briefing, The Guardian, El Pais The Mail and many others have been invaluable here and our most sincere thanks go to their journalists who are keeping this vital story at front and centre of public consciousness. In fact, If we see a journalist write a good story in this trope, we write to thank them: and beg you to do the same.

We are proud to cover other serious threats as we see them. None more so than Global Warming, which gets covered every month or so. It’s odd to recall that the fires that tore through Los Angeles in California happened nearly a year ago now (LSS 9 1 25) But they were prescient: every subsequent we made this year, to France, to Portugal, to Spain, wherever, the TV news has been dominated by ferocious fires. It was sad to discover how much of this might have been avoided(LSS 11 7 25) . As for the denialists-we thought the strange legend of The Fisher King might go some way to explaining why they feel as they do(LSS 27 10 25)

We tried to cover some more hopeful science stories as well. The progress in genetic editing techniques such as CRISPR-Cas-9 and Base Pair Editing hold out the hope for unlimited progress (LSS 19 5 25 was a working summary) and have also tried to track progress in technologies such as nuclear fusion, artificial intelligences as well as more recondite topics as evolution(LSS 19 3 25) Our usual series like Heroes of Learning and Friday Night fun have covered subjects as diverse as Fibonacci and Fish and Chips. We thought would like the new series on World Government (LSS 8 1 25 et seq) and Taxes(LSS 17 11 25 et seq) and the Best time to have been Alive (23 7 25 et seq) which by starting in China should avoid all accusations of Eurocentric bias

Of everything we covered the biggest stand out for us was the new discoveries in genetic mapping which may shed real light on the origins of psychiatric disorders(LSS 18 12 25) But for our readers it was the highly speculative Is Donald Trump a Socialist? ( LSS 7 4 25) in which we stated that, although he and his followers would recoil in horror from that label, he is acting like a socialist, however unintentionally. That one has almost never ceased to be read and commented upon. We are not sure why.

Once again thanks to all of you for your suggestions comments and ideas. It is a pleasure to read some of your blogs and postings which now cover the whole world. We in the educated community, the progressive community if you will, are few in number. But our influence is always outsize to our numbers, as it has been throughout History. You gentle reader are the hope of the world. Whatever your belief, enjoy the festivities.

#antibiotics research #microbiology #global warming #psychiatic disorders #health #medicine #environment #dona;d trump #china